By Kelan Lyons

Allowing those on probation and parole to vote marks the largest expansion of voting rights in North Carolina since the Voting Rights Act of 1965

Daquan Peters didn’t waste any time registering to vote on Wednesday. He hadn’t been fast enough last year, during a 10-day window between court proceedings when people like him — those who were home after spending time imprisoned for a felony but still on probation or parole — were briefly re-enfranchised.

This time, Peters registered on the first day he was able.

“I wanted my voice and my vote to be accounted for right then and there,” Peters said. “Because I know how wicked the system is.”

More than 56,000 North Carolina citizens who, like Peters, are on parole, probation or post-release supervision for a felony conviction could legally register to vote on Wednesday, the product of a three-year legal battle over the state’s felony disenfranchisement law. Now the only people who can’t vote because of a criminal record are those currently incarcerated for a felony.

But their access to the ballot box isn’t final; the lawsuit that won their re-enfranchisement is ongoing. Attorneys for Republican lawmakers are appealing a lower court’s ruling granting the voting rights; it is currently pending before the state Supreme Court, which could issue a decision before the November elections. A date has not yet been set for oral arguments.

However, if the lower court’s rulings stand, it could prove transformative for the 2022 elections and beyond. Superior Court Judges Lisa Bell and Keith Gregory acknowledged as much in their opinion, estimating that at least 20% of those on felony supervision — about 11,200 people — would vote if they were able.

“Given how close elections often are in North Carolina, excluding such large numbers of would-be voters from the electorate has the potential to affect election outcomes,” the judges wrote.

Election outcomes like the 2020 race for chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court: Republican Paul Newby defeated Democrat Cheri Beasley, who had been the state’s first Black woman to serve as chief justice, by a mere 401 votes.

Beasley, who is running for U.S. Senate, could still benefit from a surge of new voters in a tight race this November.

Before the state Supreme Court agreed to take up the appeal, attorneys for Republican lawmakers submitted court documents arguing that the injunction ordered in the Superior Court opinion, “issued on the eve of statewide primary elections, was a plain violation of the principle that courts should not rewrite election rules on the eve of elections.” They also said the court had “misread legislative history,” since the statute challenged in the lawsuit had in fact lowered the barriers those convicted of felonies face when trying to regain their right to vote.

Restoring the voting rights of more than 56,000 people could have “seismic implications,” said Brittany Cheatham, communications coordinator for Forward Justice, one of the organizations that represents the formerly incarcerated plaintiffs in the lawsuit. “I think that’s a part of the reason why folks are fighting so hard not to re-franchise these people,” said Cheatham.

“They’re scrambling, and they’re going to do everything in their power to be able to try to not make this a historical mark in North Carolina,” Peters said. “Especially led by people that look like us.”

A history rooted in racism

The opinion written by Superior Court Justices Bell and Gregory delved deep into the history behind felony disenfranchisement in North Carolina — and how it still disproportionately locks Black voters out of the ballot box.

Black people make up 21% of North Carolina’s voting-age population, the judges note, but over 42% of those who are ineligible to cast a ballot because of felony probation, parole or post-release supervision.

Whites, meanwhile, make up 72% of North Carolina’s voting age population, but just 52% of those denied the right to vote.

That wasn’t a mistake. It was by design.

Bell and Gregory’s 65-page opinion states that, after the Civil War, North Carolina adopted a new constitution so it could rejoin the union. The delegates at the 1868 Convention — around 15 of the 120 of whom were Black, among others who were in favor of racial equality — approved a constitution that allowed all males to vote and eliminated property requirements as a condition of voting eligibility. It did not contain a provision that barred people from voting if they were convicted of a felony.

Especially enraged by the universal right to vote, white supremacists reacted violently. The Ku Klux Klan murdered Black elected officials and white Republicans alike. They also, the judges note, “engaged in a campaign of fraud and violent intimidation of African American voters.”

In the late 1860s, white former Confederates engaged in a widespread campaign of convicting Black men of petty crimes, then whipping them. This allowed the former Confederates to take advantage of a law that disenfranchised anyone subjected to the punishment of whipping.

With scores of Black men unable to vote because of white disenfranchisement efforts, white Democrats took control of the state legislature in 1870. Five years later, they called a constitutional convention to amend the 1868 Constitution, approving a slew of racist measures that subjugated Black citizens and diluted their political power in the name of white supremacy. One of the amendments disenfranchised anyone “adjudged guilty of felony.” This was the first time in North Carolina history that state allowed the disenfranchisement of people convicted of any felony. State lawmakers codified the felony disenfranchisement into law in 1877.

“The 1877 law did not just disenfranchise people with felony convictions, it also continued that disenfranchisement even after those individuals were released from incarceration and living in North Carolina communities,” Bell and Gregory wrote.

Those who voted before their rights were restored — an onerous process that deferred to the discretion of judges who had to be petitioned for re-enfranchisement — were fined up to $1,000 and potentially imprisoned for up to two years. At the time, the per capita income of Blacks in the South was $40.01, the opinion notes.

State lawmakers reached a compromise in the early 1970s to restore voting rights to individuals convicted of felonies who had finished their terms of probation and parole. The Superior Court judges noted that it is “clear and irrefutable” that the goal of the three African American legislators who introduced the bill in the ’70s was to end the disenfranchisement of people who had been sent home from prison following a felony conviction, “but that they were forced to compromise in light of opposition by their 167 White colleagues to achieve other goals, such as eliminating the petition requirement.”

But those revisions maintained three key provisions of the 1877 legislation: the disenfranchisement of all people with a felony conviction, not merely those convicted of certain crimes; the criminal penalty for voting before the rights are restored; and the denial of the right to vote for people with a felony on their record and who are not imprisoned but are living at home.

The law, the judges wrote, “continues to carry over and reflect the same racist goals that drove the original 19th century enactment.”

“Elections cannot faithfully ascertain the will of all of the people when the class of persons denied the franchise due to felony supervision is disproportionately African Americans by wide margins at both the statewide and county levels,” they wrote.

The North Carolina Court of Appeals partially granted legislative leaders’ request for a stay in a ruling issued on April 26, 2022. But that stay was only in place for the primary elections on May 17 and July 26. Now, the State Board of Elections must implement the order outlined in Bell and Gregory’s opinion: that all citizens who are living in the community with prior felony convictions must be allowed to register and vote.

Unlocking the vote all summer

With the people on felony supervision still eligible to register and vote, the race is on to not only to register thousands of voters, but also to convince them of the importance of casting a ballot.

To that end, a broad coalition of criminal justice advocacy organizations gathered in Raleigh on Wednesday to kick off the “Unlock our Vote Freedom Summer” tour. Over the next 14 weeks, organizers will host voter information and registration events across North Carolina, in Alamance, Buncombe, Craven, Durham, Mecklenburg, Pitt and Wake Counties, among others.

Despite the potential to swing elections, Cheatham said the goal of the voter registration drives was not to put one political party in power over another, but to empower “Second Chance voters” who have remained disenfranchised even after finishing their prison sentences.

“This is not partisan,” Cheatham said before the gathering. “This is, ‘Just because you had involvement with the legal system does not take away your right to have a voice in how you’re governed. Especially when you’ve done your time.’”

Peters, now the New Hanover County Second Chance Alliance coordinator and an organizer for Forward Justice, was among those who spoke Wednesday afternoon. Nearing age 50, Peters has spent almost half of his life behind bars. His political awakening came after he was sentenced to almost 22 years in federal prison for giving someone a free half-ounce of crack cocaine. While incarcerated, he learned about the racist history behind another law — the sentencing disparity between those convicted of charges related to crack versus powder cocaine. Peters became convinced that it was vital to vote so he could help uproot unjust laws and the politicians who support them.

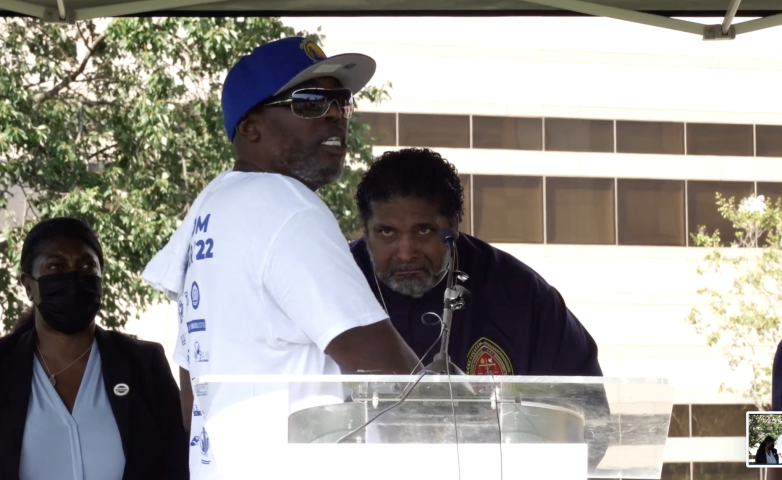

Wednesday was an emotional day for Peters, not just because he could register to vote, but because of who was standing there with him. When Peters was locked up, he followed the work of Rev. William J. Barber II, founder and president of Repairers of the Breach and co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign. Peters subscribed to The News & Observer to follow the reverend’s work, and was deeply moved by his commitment to freedom, justice and equality.

Barber gave Peters hope that people outside prison walls cared about him.

“We don’t think that people be out there fighting for us like this on the front line,” said Peters.

The two men met for the first time on Wednesday. Barber spoke just before Peters, saying that allowing people on felony supervision to vote was the largest expansion of voting rights in North Carolina since the 1960s. The next task, Barber said, was to turn that into historic turnout for the midterms.

“Now these votes must be registered and utilized. They must be registered and cast. They must be registered and counted,” Barber said. “We’ve got power to change America. We’ve got power to change North Carolina. And we intend to use all the power that God has given us.”

Before Peters told his story, he hugged Barber and told the crowd how much Barber’s message meant to him when he was locked in a cell. He talked about the fight ahead to translate voting rights into political power. He addressed the role of volunteers with similar life experiences in convincing people on felony supervision that they have power they can wield in the ballot box. Then he seemed to turn his attention to those he deemed enemies of equality.

“What is the fear of us voting? What do you fear?” Peters asked, offering an answer: “The same thing you’ve been fearing our whole existence in America: that if we ever come together, if we ever say, ‘Hey, you know what, we’re gonna break these chains of psychological slavery that you got us imposed with now, and we’re gonna come together, and we’re gonna get your butt up out of there.’”