An anthropologist of Japanese religion met followers of Shinto religion online and found how they were building a community and sharing instructions on practice.

CC BY-NC-SA)” >

CC BY-NC-SA)” >

(The Conversation) — American Kit Cox, 35, works as an electrical engineer and enjoys biking and playing piano. But what some might consider surprising about Cox, who was raised as Methodist, is that she practices the Japanese religion known as Shinto.

While Cox’s interest in Shinto was originally sparked by her love for Japanese popular culture and media, Shinto practice is not just a phase or fad for her.

For over 15 years, she has venerated Inari Ookami, a Shinto deity or “kami” connected to agriculture, industry, prosperity and success.

After several years of study, Cox received a great honor from Fushimi Inari Taisha, one of Japan’s most popular Shinto shrines. She was entrusted with a “wakemitama,” a physical portion of Inari Ookami’s spirit, which is now housed in a sacred box and enshrined in her home altar.

What’s more, Cox has emerged as a leader within a relatively small but growing community of Shinto practitioners scattered around the world. Her goal: to help Japan’s “indigenous” religion go global.

As an anthropologist of Japanese religion studying the spread of Shinto around the world, I met Cox where most non-Japanese people interested in Shinto do – online. Over several years of studying social media posts, participating in livestreams and conducting surveys and interviews, I’ve heard many people’s stories of what draws them to practice Shinto and how they navigate the difficulties of doing so outside of Japan.

What is Shinto?

Shinto has many faces. For some, it is a reservoir of local community traditions and a way of ritually marking milestones throughout the year and in one’s life. For others, it is an institution that attests to the Japanese emperor’s divine status as a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu or a life-affirming nature religion.

But at its core, Shinto is about the ritual veneration of kami.

A statue of a fox messenger at the Grand Shrine of Fushimi Inari in Kyoto, Japan.

WKC/flicker, CC BY-SA

These myriad deities can take different forms. Many are associated with features of the natural world, like lightning and the sun, while others look after human concerns, from marital relationships to acing one’s college exams.

One of Shinto’s primary concerns is the management of spiritual impurities through ritual purification. According to Shinto thought, impurities accumulate simply as a product of living in this world, as well as through contact with sources of impurity, such as death or disease, and committing inappropriate acts. Because spiritual impurities offend the kami and are capable of threatening social order and people’s well-being, Shinto priests must purify them regularly through ritual.

Besides purification, Shinto also provides what contemporary Japanese religion experts Ian Reader and George Tanabe Jr. call “practical benefits.” These innumerable benefits include good health, prosperity and safety.

At Shinto shrines and in other sacred spaces, both priests and regular folks from all walks of life perform rituals to express gratitude for the deities’ protection and pray for their continued blessings.

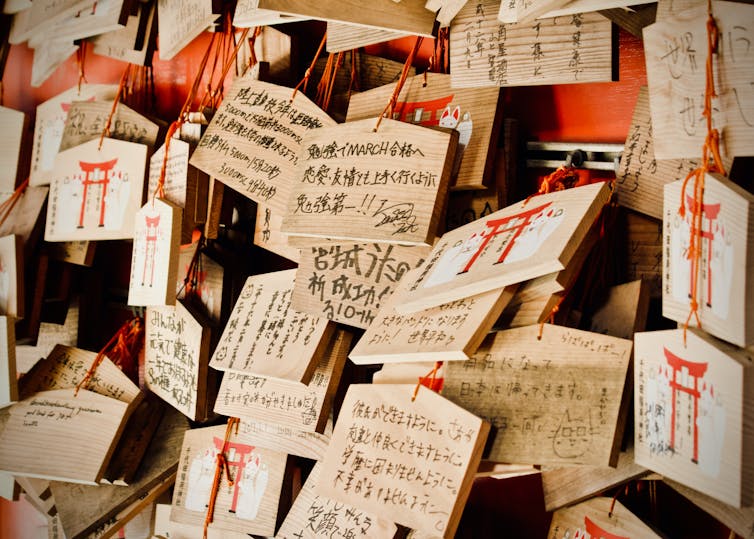

Petitioners write messages to the Shinto deities on wooden prayer boards.

Jelleke Vanooteghem/Unsplash, CC BY

Why do people choose Shinto?

While Shinto is often characterized as the “indigenous” religion of Japan, it is not limited by geography, nationality or ethnicity.

Non-Japanese people have received certification as Shinto priests, and Shinto shrines can be found around the world, including in the United States, Brazil, the Netherlands and the Republic of San Marino.

Global practitioners stress that, unlike many organized religions, Shinto has “no founder, doctrine, or sacred texts.” The majority identify as “spiritual but not religious,” a growing category of people who define spirituality as “personal, heart-felt, and authentic,” as opposed to the hierarchy and dogma of institutional religion.

A Shinto shrine outside Seattle. Researched by Kaitlyn Ugoretz and co-written by Ugoretz and Andrew Mark Henry.

For people of Japanese descent, Shinto rituals often provide a way of maintaining relationships with ancestors and a connection with their cultural heritage. As I found during my field research, non-Japanese practitioners find Shinto particularly appealing for a number of reasons.

First, Shinto reflects their values: a positive perspective on life, a focus on gratitude and harmony, care for the environment and compatibility with other traditions. Members find the community welcoming to people of diverse gender identities, sexual orientations and abilities.

Second, they appreciate Shinto’s focus on ritual. Cox jokes that if she were to be a Christian, she would probably be a Catholic for the rituals. Shinto practitioners describe rituals as an opportunity to reflect, reconnect with the divine and renew or refresh their own spirit.

Third, Shinto provides a way to engage more deeply with Japanese culture. Many practitioners first encountered Shinto through anime, video games, martial arts or tourism. Some Shinto priests even use popular culture as a teaching tool, performing rituals and giving lectures at cultural events and fan conventions.

What does the online Shinto community look like?

Much to my surprise when I began my digital research, I found that online Shinto communities have existed since the birth of the internet as we know it today.

In 2000, the “Shinto Mailing List” was created on Yahoo Groups (now defunct) as a space for over 1,000 people to discuss Shinto with like-minded individuals. Fast-forward 20 years, and Shinto communities include some six to 10,000 members hosted across several Facebook groups, other social media platforms and even virtual worlds.

As my research shows, Shinto priests and lay practitioners use social media to talk about their experiences and ask questions. The most frequently posed questions by new members are “Is it okay to practice Shinto as a non-Japanese person?” and “How exactly do we practice Shinto outside Japan?” They also create and share resources, such as guides for ritual practice at home, recommended books and other media, and instructions on how to contact and support Shinto shrines.

Some Shinto priests are very active on social media.

Kaitlyn Ugoretz, CC BY

While internet-based religion is considered taboo by the majority of Shinto shrines in Japan, some overseas shrines, such as Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America and Shinto Shrine of Shusse Inari in America, have created their own vibrant online shrine communities. They share news on upcoming events and livestream monthly and yearly rituals and festivals. They both have active social media presences, and Shinto Shrine of Shusse Inari in America is even exploring alternative forms of fundraising via crowdfunding sites like Patreon.

A day in the life

Since most practitioners outside of Japan do not live near a Shinto shrine, their everyday ritual practice focuses on venerating the Shinto deities in their home at an altar called a kamidana or “kami shelf.”

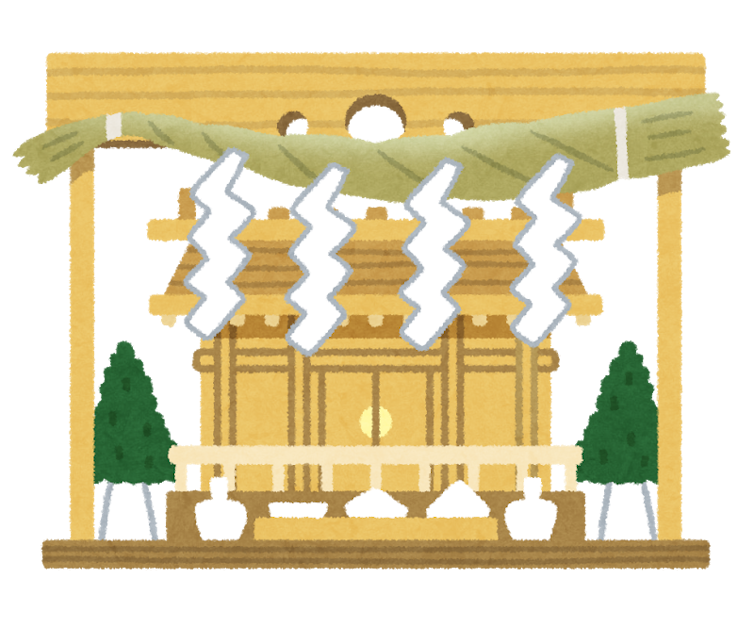

Illustration of a typical Shinto home altar (kamidana).

https://www.irasutoya.com/, CC BY

In the morning, Cox greets Inari Ookami with a series of deep bows and claps. She recites prayers called “norito” and puts out traditional offerings of rice, water and salt in gratitude for the kami’s blessings.

In the evening, she removes the offerings and consumes them. This practice is meant to bring humans and divinities closer together by sharing the same meal. It’s also a great way to avoid wasting food.

Some offerings can be hard to come by outside Japan. In these cases, Shinto practitioners may offer similar, local substitutes, such as oats instead of rice. They may also make creative additions to their altars, personalizing the space and their relationship with the kami.

Others have difficulty sourcing the materials required to set up a Shinto altar, especially the sacred “ofuda” talisman, which must be received from a shrine. They may build their own altars or pay their respects at a digital altar in an app.

What’s most important, according to Cox, is respect for tradition and the sincerity of one’s intentions and actions. Slowly but surely, as Shinto spreads around the world, practitioners are making it their own.

<p

(Kaitlyn Ugoretz, PhD Candidate, East Asian Languages and Cultural Studies, University of California Santa Barbara. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)