WASHINGTON — The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is processing claims at the fastest rate […]

Category: medical

Governor Roy Cooper Comments on Judge Reinstating 20-Week Abortion Ban

Raleigh Aug 17, 2022 Today, Governor Roy Cooper issued the following statement in response to […]

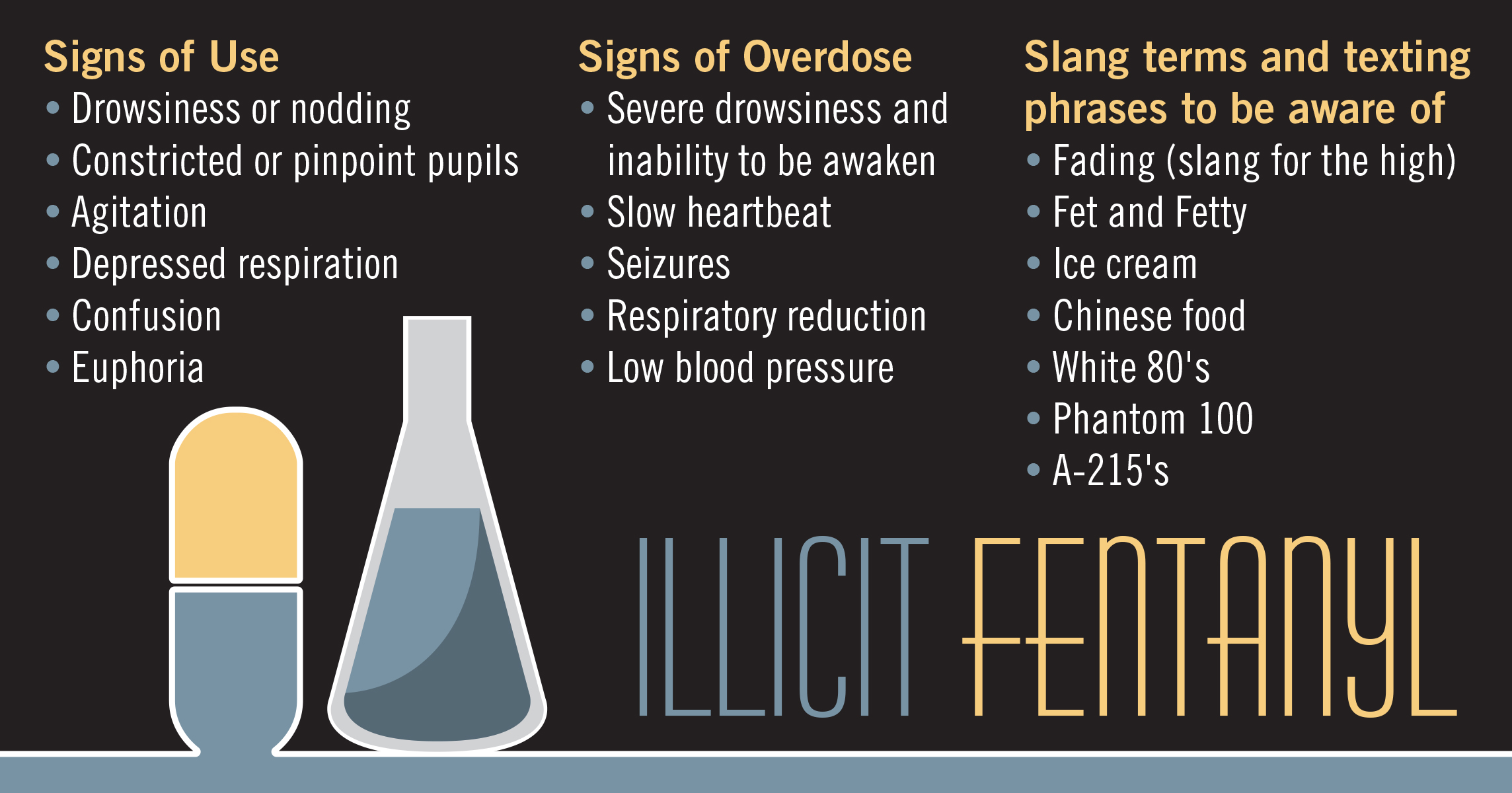

Fentanyl in NC: An epidemic within the opioid epidemic

By Joe Killian – 8/15/2022 NC Policy Watch A year ago this month, Barb Walsh […]

Winterville woman charged with seven counts of Insurance Fraud

RALEIGH Jul 29, 2022 North Carolina Insurance Commissioner Mike Causey today announced the arrest of […]

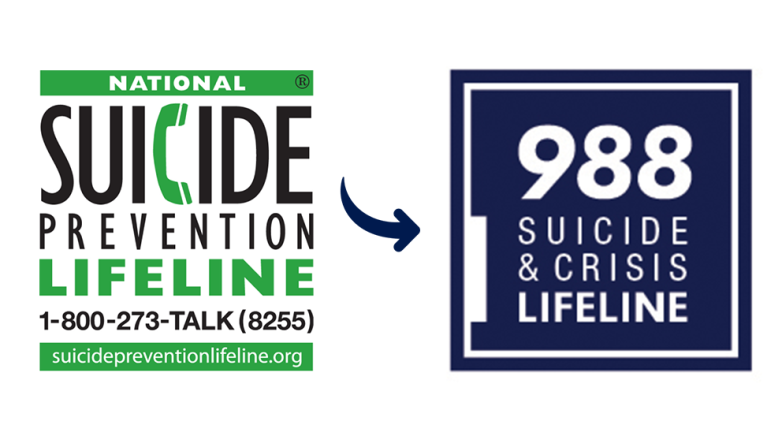

The Lifeline and 988

988 has been designated as the new three-digit dialing code that will route callers to […]

NCDHHS Again Expands Eligibility for Monkeypox Vaccination, Encourages Steps to Reduce Spread

“Get Checked. Get Tested. Get Protected.” Raleigh Jul 25, 2022 The North Carolina Department of […]

Hampered by opposition from doctors’ groups, nurse practitioners want to change state law to give them more freedom to treat patients

By Lynn Bonner – 4/7/2022 NC POLICY WATCH Michelle Skipper has a doctorate in nursing practice and […]

Rural healthcare providers feel the pain of North Carolina’s Medicaid gap

By Lauren Ketwitz – 3/22/2022 NC POLICY WATCH On her morning commute to work, Dr. Laura […]