Political gerrymandering is dead in North Carolina, at least for now.

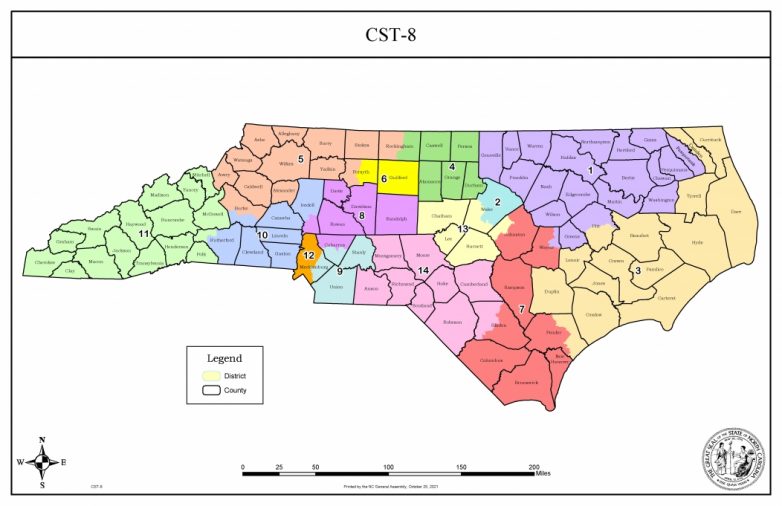

The state Supreme Court issued an order late Friday striking down the Republican-drawn political maps slated to be used for the rest of the decade. Groups challenging the maps hit a grand slam, winning on each of their constitutional claims.

A 4-3 majority of the Supreme Court found that the state legislative and congressional maps were “unconstitutional beyond a reasonable doubt under the free elections clause, the equal protection clause, the free speech clause and the freedom of assembly clause of the North Carolina Constitution,” according to the order, written by Democratic Justice Robin Hudson.

The General Assembly will have to redraw maps and submit them by noon Feb. 18 to a three-judge panel in Superior Court for approval.

If the panel decides the General Assembly’s new maps don’t meet the court’s new standards, it can select maps submitted by the groups who sued the state. Whatever the trial court selects, the state or any of the challengers can appeal the decision by 5 p.m. Feb. 23.

That’s the day before candidate filing is set to open again, so there is a chance North Carolina will see a repeat of what happened in December, when the courts shut down candidate filing — then reopened it, then shut it down again.

Because of the tight timeline, the Supreme Court only issued an order, not an opinion, meaning that it told the relevant groups what they had to do next but did not describe the full legal justifications underpinning the decision. The opinion will be submitted later, according to the document.

Chief Justice Paul Newby, a Republican elected in 2020, expressed his frustration with the decision in a snappy dissent, writing that the Democratic-majority court interpreted the constitution in such a way that left “no limits to this Court’s power.”

Since the state constitution does not put an explicit limit on partisan gerrymandering, Newby argued, the only ways to do so are by statute or a constitutional amendment. Both would require the legislature to act to limit its own authority to draw partisan maps.

Either the General Assembly takes the Supreme Court’s order and attempts to draw constitutional maps or takes the risk that the courts will choose maps submitted by the groups that sued. It will also have to submit the data it used to draw the maps and the methods used to measure partisan fairness.

The Supreme Court recommended, but did not require, five different metrics for measuring the partisan fairness of a map.

“To comply with the limitations contained in the North Carolina Constitution, which are applicable to redistricting plans, the General Assembly must not diminish or dilute any individual’s vote on the basis of partisan affiliation,” the majority wrote.

But Newby wrote those guidelines are “vague and undefined,” meaning only the court itself will be able to define the constitutionality of new maps.

“The question of how much partisan consideration is unconstitutional remains a mystery, as does what is meant by ‘substantially equal voting power on the basis of partisan affiliation,’” Newby wrote.

The Republican-controlled legislature, which drew the maps and whose leaders are the named defendants in the case, can partially appeal the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, at least regarding the congressional map.

Though it’s speculation, that appeal is likely, according to Catawba College political science professor Michael Bitzer.