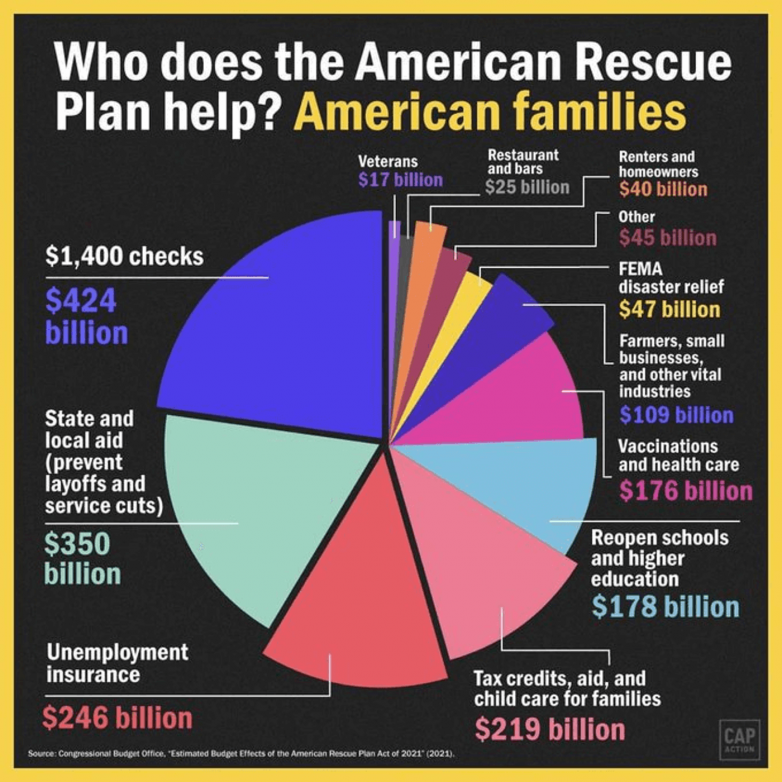

To conclude its ARPA reporting project, CPP looks into how other ARPA funds, the $5.4 […]

Author: Carolina Public Press

As NC’s decades-old rape kits are tested, new DNA evidence emerges

The N.C. Attorney General’s Office now has a website that tracks kit testing and arrests. […]

Fort Liberty: Divided views on changing Fort Bragg’s name

Fort Bragg may soon go by another name: Fort Liberty. In last year’s National Defense Authorization […]

Waiting for the feds: Some NC counties sat on ARPA funds for months due to unclear rules

By Shelby Harris Carolina Public Press American Rescue Plan Act funds first reached local governments in May […]

Internet-starved counties see hope for broadband in ARPA funds

Residents excited at the potential to have access, but county officials planning to leverage federal […]

Why small NC mountain city is taking on nation’s largest hospital system

Brevard officials hope other Western NC local governments will join lawsuit alleging monopolistic practices by […]

Shoring up Lake Tomahawk dam with ARPA funds

Black Mountain hopes to extend life of 90-year-old earthen dam using $300k from its share […]

Lake Lure using ‘providential’ ARPA funds to start massive sewage repairs

Aging sewer system under the town’s namesake lake will take $60 million to replace over […]

Some NC agencies slow to turn over details of leaders’ daily schedules

Sunshine Week project examines responsiveness and transparency of top state officials receiving requests for records. […]

Henderson County invests ARPA funds in clinics to fight pandemic

Antibody infusion clinics at Advent Hendersonville and Pardee Hospital receive $500k to help treat COVID-19 […]